WHY DO YOU CRY TO ME? BETTER SING! – by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

The 13ththru 17thchapters of Exodus tell some of the Bible’s most dramatic and significant episodes. After unsuccessfully negotiating with Moses, Pharaoh and his people experienced the last three plagues, starting with Locusts, #8, then Darkness, #9, and finally #10, the most fearsome of all, Death of the Firstborn. Again Pharaoh tries negotiating after 8 and 9, but fails. When his own firstborn, the heir to the throne, is found dead – as well as every firstborn of humans and cattle in Egypt – he officially ejects the entire Hebrew nation, adults, children, livestock and all. Off they go.

But before they can reach the Red Sea, Pharaoh has another “change of heart.” What was he thinking? How could he send away all those slaves? So he mobilizes 600 shock troops – chariots and horsemen – and gives chase. Seeing the cloud of dust raised by the pursuing army, the Israelites turn on Moses: “Were there no graves in Egypt? You had to bring us here to die in the desert?” Moses assures them that G-d will fight for them, and they are to be silent. And indeed the Divine pillar of cloud moves from in front of the Israelites to behind them and hovers between them and the Egyptian army.

Now they arrive at the sea shore. What can they do? Like his people, Moses sees a grim alternative: get slaughtered by the enemy or drown in the sea. Moses cries to G-d for help, and gets the Divine retort: Mah titz’ak ey-lai? (We can almost hear Jewish parents asking the same question in Yiddish: Vos shry’stu af mir?) Moses hears:“Why do you cry to me? Tell the Israelites to move forward.” Here a famous midrash supplies the details. Nothing happens until one man, Nachshon by name, steps into the water. He goes forward until the water reaches his neck, and then – the great miracle! A powerful wind raises the water to a wall on his right and on his left, and the Israelites cross on dry land. In his honor, the name Nachshon survives in modern Israel as the example of courageous action.

The pursuing Egyptian chariots lose their wheels in the deep wet sand, and their riders die in the sea. The lost wheels of the royal chariots were overlaid in gold. Just recently archeologists found those gold wheel-covers at the bottom of the Red Sea. The wooden wheels and the chariots themselves were long since decomposed, but the metal survived! Yes, it really happened.

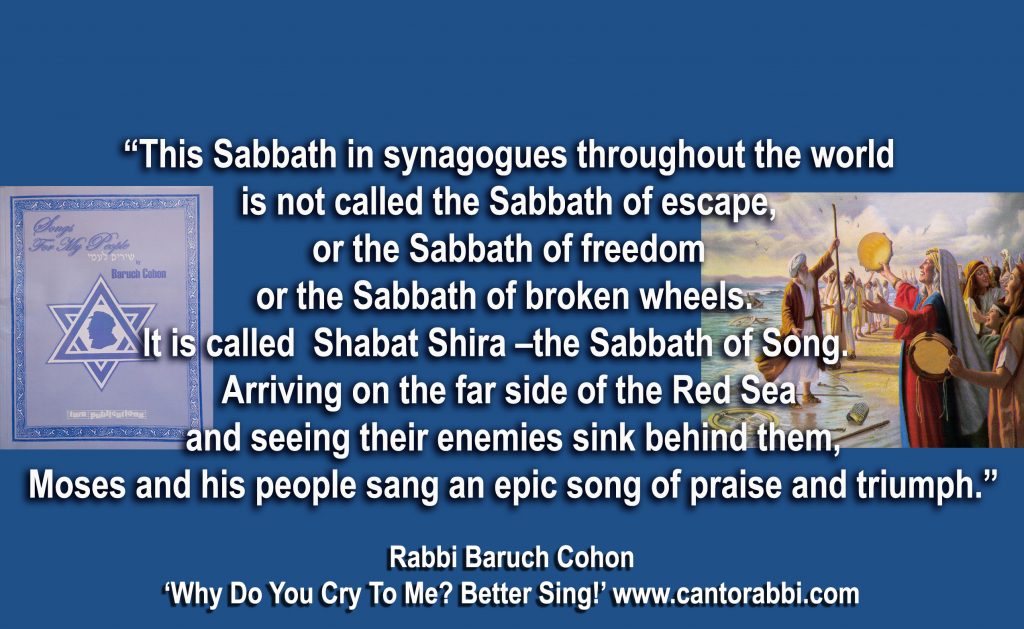

None of these episodes, spectacular as they are, give their name to this reading, however. This Sabbath in synagogues throughout the world is not called the Sabbath of escape, or the Sabbath of freedom or the Sabbath of broken wheels. It is called Shabat Shira –the Sabbath of Song. Arriving on the far side of the Red Sea and seeing their enemies sink behind them, Moses and his people sang an epic song of praise and triumph. This Song of the Sea is still chanted with its special melody in this week’s Sabbath morning services. And this Sabbath provides an occasion to perform Jewish music old and new for many audiences.

Of course the story goes on, as the 40-year trek through the desert is just starting. In fact, at the end of this section we see the cowardly tribe of Amalek – the jihadists of their day – attack Israel, striking from the rear. A fierce battle ensues. We will read how Moses climbs a hill and holds his sacred staff up high, with Aaron and Hur flanking him, while on the plain below Joshua leads the fight against Amalek. As the day goes on, Moses’ arms tire and Aaron and Hur have to hold them up so the fighters can see the symbol. As long as they can look up, they prevail. Only when they look down do they risk losing. Courage and confidence lead them to victory, A symbolic tale if there ever was one.

Among the symbolic stories in this section, one word that gets very little mention – and even gets an inexact translation – appears in Chapter 14 verse 30. The standard English translation reads: “The Israelites saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore.” But that’s not what the Hebrew text says. The word for Egyptians would be mitzrim, but the Hebrew says mitzra-yim, which would translate: “Israel saw EGYPT dead.” Not some soldiers floating in the water, but the death of the Egyptian empire. After defying destiny and denying freedom, Pharoah succeeded only in leading his nation to defeat. Indeed the ancient power of Egypt never recovered. King Tut’s fame and the Suez Canal and the Aswan Dam are all the work of foreigners. Even the population changed when civilized Egyptians were overrun by Mohamed’s primitive tribesmen. Truly Israel saw Egypt dead.

Another significant word-form starts the Song of the Sea. The Hebrew does not say Az sharMosheh – “Then Moses and the Israelites sang,”but Az yashirMosheh – “Then Moses and the Israelites will sing,” a hint that our great song is yet to come, when we will all sing with the Moshiach – the Messiah, who will bring G-d’s kingdom to Earth.

Many of us are still waiting.