WHO’S HOLY? – Ahrey Mot-K’doshim Lev. 16-20 by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

Just as they did last week, this week synagogue Torah readings cover two sections. They get combined except during leap years. In fact, they go together well. Last week’s double bill concentrated on the issues of purity and contamination. This week we read about laws and penalties.

First, however, the Torah lays out the conduct of the Yom Kippur service in the ancient sanctuary, including the sacrificial offerings, the conduct and clothing of the High Priest, and of course the scapegoat ritual.

Then come some detailed directions for slaughtering, preparing and eating meat. One outstanding provision is not to eat the blood. No “steak juice” cocktails allowed. Consuming an animal’s lifeblood had idolatrous associations, and we are told to pour it on the ground like water.

The remainder of the first section details actions to be avoided, citing them as typical of the corruption of Egypt. Included here are prohibited degrees of sexual contact, from incest to bestiality and, yes, homosexual relations. Polluting the Promised Land with such conduct would cause the land to “vomit you out, as it did the nation who was there before you.”

Warnings and prohibitions are not enough. The second section, called K’doshim – “Holy ones” – sets out penalties for violating these laws. We don’t find any prison time mentioned here. No fines, either. Minor infractions call for burnt offerings. Major violations incur execution or ostracism. Torah law may not be politically correct. Too bad. But what does all this strict punishment have to do with holiness?

In its very special way, the Torah defines Holiness before even going into detail about punishment. To be holy does not mean setting yourself apart from human society and its temptations. No ivory tower. Don’t try to be what’s called a “holy Joe.”

Just the opposite, in fact. Holiness requires that we deal justly and respectfully with each other. Honor your parents. Keep the Sabbath. Pay a day-worker before nightfall. Do not deceive your neighbor or lie, and never swear falsely because that is blasphemy. Do not curse the deaf, or place a stumbling block in the path of the blind.

Judges may well note the ruling: “Do not favor the person of the poor and do not glorify the person of the mighty. Judge your neighbor with justice.” Principles like those apply to non-court situations too, as we read about relations with someone whose actions you disapprove: “Do not hate your brother in your heart. Rebuke him, and do not bear sin because of him.”

Perhaps the most down-to-earth expression of holiness is this: “Do not take vengeance or bear a grudge against one of your people.” The classic examples of this disapproved conduct goes this way: Vengeance is when you ask to borrow your neighbor’s axe and he refuses; then next week he asks to borrow your ladder and you refuse, saying “You wouldn’t lend to me, so I’m not lending to you.” A grudge is when he refuses to lend you his axe, but when he comes to borrow your ladder you say: “Sure, here it is. You see? I’m not like you!”

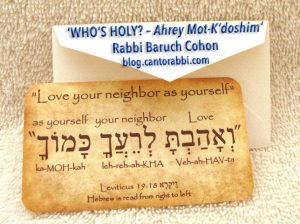

Most famous of all the holiness teachings is the line “Love your neighbor as yourself.” To me, this means that first you need some self-love. If I have no respect for myself , what value is my love for my neighbor? Of course, the process goes both ways. By building a habit of treating other people right, we can also take some pride in our own lives.

Who is holy? Potentially, you and I.