Shabbat Times

Powered by Hebcal Shabbat Times- Powered by Hebcal Shabbat Times

Top 50 Jewish Blog by Feedspot

The Head by Baruch Cohon

THE HEAD

In the Navy, the men’s room was called the Head. And on WW2 ships it

was exclusively a men’s room. But that was the first American war

when women who were not nurses were actually admitted to the armed

forces. Accordingly, a cartoon from those days comes back to me. Not

a cartoonist, I can’t draw it, so I’ll develop it:

Urinals in the “head” were attached to the bulkhead (that’s the wall

on a ship) and they stuck out at a height of at least 2 feet. In the

cartoon, a sailor is using one urinal, and at the one next to him a

short gal in a WAVE uniform is busy hoisting one leg over the urinal.

To his unspoken comment she says: “Well, I’m doing a man’s job,

ain’t I?”

It was funny in 1943. Little did we know how prophetic it was. All

Gender bathrooms go with a policy that sets a goal of equality in

employment. No more men’s jobs and women’s jobs. Stay-at-home wives

used to be respected as homemakers. Now they are in a snubbed

minority. Makes anyone my age wonder about the future of the American

family. Maybe more gals are doing men’s jobs, but who’s doing the

women’s jobs?

No matter how “progressive” they are, male Americans don’t seem to be

able to bear babies. So how can they reproduce? In many cases

their reproductive value is limited to supplying nameless semen to

impregnate one or the other member of a female “marriage.”

Biblical statements are sometimes difficult to understand, but here’s

one that is perfectly clear: “Male and female created He them.” It

applies to animals, birds, fish, insects – and humans. We don’t see

other forms of life trying to deny their sex. Maybe they know

something we don’t know?

Young people maturing in a confused world like this understandably

take their time making any relationship permanent – or productive.

Any thought of building a family is pretty far down on their scale.

That does not keep them from sex. Or from reproduction. Recent

statistics list some 23% of white babies and 73% of black babies as

born out of wedlock. City fire stations get a steady influx of

unwanted infants, and have a system to keep them alive. But our

national population is damaged by a decreasing birthrate, and an

increasing crime rate involving many of those boys who got delivered

to the fire station, only to grow up on the street and have no fathers

to raise them.

So what do we need to do? Reverse our direction and put all the women

back in the kitchen?

Not hardly. Our girls go to school just like the boys. They find

interests and careers in business and industry, in government and

education. They bring real talent to their employers and valuable

service to the public. Are they “doing a man’s job?” You bet.

Sometimes better than the men they replace. And if they can also

build a family with a beloved mate, they are also doing a woman’s job.

Many women succeed in doing both. And hopefully more men will accept

their wives in both areas, and join them to keep the house clean and

put food on the table and, yes, to supervise their kids – to build

homes and families and a balanced future.

Somehow change never seems to come without pain. Old habits are hard

to break. But a little understanding can ease the pain and help the

change. Let’s try for that.

Posted in Jewish Blogs

|

Tagged Baruch Cohon, Blog, Blogs, Change, child rearing, Children, Doing a man's job, equality, families, Family Values, Gender Equality, home, Parenting, Parents, woman's role

|

Comments Off on The Head by Baruch Cohon

COUNTING IN THE DESERT – Bamidbor – Numbers 1-4:20, by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

COUNTING IN THE DESERT – Bamidbor – Numbers 1-4:20, by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

This week’s reading gives its name to the entire book which it opens. But the English name seems to bear no relationship to the Hebrew name of the same book. “Numbers” is not a translation of “Bamidbor,” which means “In the desert.” Actually, the Hebrew name sets the scene for the whole history described in this book, which follows the ancient Hebrew tribes through the desert, in their slow and perilous progress toward the Promised Land. The English name is appropriate to this week’s reading, however, since here we see the completion of the census Moses conducted just a couple of months earlier when the Tabernacle – the mishkan – was built. Then, every male Israelite of military age had to bring a contribution of half a shekel toward the construction of the first Jewish house of worship. By counting the coins, the people’s leaders knew the total number of potential fighters: 603,550.

Now Moses has to fill in the details. How many in each tribe, who will lead each tribe, where will each tribe camp, etc. The total here is identical with the total in the half-shekel count in Exodus 38:26. But the purpose of this census is different. Besides joining in a religious cause, the men of Israel are now registering for the draft – the IDF of Moses’ time — accepting responsibility for the safety of their camp, and acknowledging the authority of their tribal chiefs. In effect, this census – this re-count if you will – marks another step in developing both civil and military structure. Ancient Israel is becoming a nation. Not without pain, to be sure. Further along in this book of Bamidbor we will see their trials, tragedies, triumphs – all the milestones and missteps on the way to nationhood – even before crossing the Jordan. Each tribe is numbered here, from the largest, Judah at 74,600, to the smallest, Menasheh at 32,200. Only the tribe of Levi is not numbered since the men of Levi had military exemption; they did not serve in the army but were devoted to Tabernacle service. In fact they camped closest to the Tabernacle on three sides. And the families of Moses and Aaron camped on the east side. Rashi’s commentary points out that their neighbors on the east side of the camp were the tribes of Judah, Issachar and Zebulun, and because of that proximity those tribes produced great Torah scholars! Thus we learn about the great value of a good neighbor. So observes the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Another feature of this week’s reading should not be overlooked. We will read that G-d spoke to Moses and the Israelite people in the desert. A place of danger! That is where they went when they left Egypt, without provisions, without protection, without plans. All they took with them was courage. Faith in G-d, confidence in themselves, perhaps a “here goes nothing” feeling that this is a chance they have to take. Certainly they were not above challenging Moses. Certainly they had to wait for one of their own leaders, Nakhshon ben Aminodov, to wade into the Red Sea before they could cross on dry land. Yet they moved ahead into a barren wasteland with no guarantees of success – or even of survival. Guts like that could impress the Divine. And so our ancestors received the Torah, and built the Mishkan,the portable sanctuary that served as their spiritual center for 40 grim years. To such a brave nation – despite their quarrels, their doubts, their mistakes – Moses brought G-d’s word. In the desert.

Some deserts bloom today, because the descendants of that nation make them bloom. And some of those descendants face challenges today that equal those of Moses’ time. In a way, we’re all in the desert. Like the nation that marched into Sinai, let us earn the Torah’s message – and learn that message, to implement it in our lives. It can strengthen us to achieve victory over enemy violence and self-defeating doubt. We were counted in the desert. Count us in now, everywhere.

Posted in Jewish Blogs

|

Tagged Aaron, Bamidbor, Book of Numbers, Census, Count, In the Desert, Israel, jewish, Jewish Blogs, Levi, mishkan, Moses, Nakhshon ben Aminodov, Numbers, Rabbi Baruch Cohon, shekel, Tabernacle, Torah, Torah Blogs, Torah Study, Tribes

|

Comments Off on COUNTING IN THE DESERT – Bamidbor – Numbers 1-4:20, by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

TO PROFANE OR TO SANCTIFY – “Emor” – Lev. 21-24 – by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

TO PROFANE OR TO SANCTIFY – “Emor” – Lev. 21-24 – by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

The section called “Emor” – literally “Say!” – will be read this coming Shabat in traditional congregations outside of Israel. It was read last Shabat in Israel and in Reform congregations elsewhere. Just a calendar discrepancy. Personally, of course, I feel a special connection to “Emor” because I read this section at my own Bar Mitzvah. That was a long time ago, but the message of this reading rings just as strongly in my ears today.

Opening with some detailed rules and regulations for the priests – the Cohanim, Aaron’s sons and descendants – from their personal conduct to their sacrificial duties, and continuing with the entire sequence of the Jewish religious calendar, “Emor” is quoted at other times of the year besides these two weeks. In Chapter 23, for example, we read the sequence of counting the Omer, the very period we are in right now, leading us from the freedom holiday of Passover to the anniversary of becoming a nation on Shavuot. Which by the way always comes at the same time in Israel or outside of it.

Between these two sections, we find two short sentences that give all these laws their basis. They come at the end of Chapter 22. Verse 31 says: “Keep my commandments and do them; I am G-d.” And verse 32 adds: “Do not profane My holy name, and I will be sanctified among the Israelites; I am G-d who sanctifies you.” Divinely inspired rules that, if we follow, enable us to achieve Kiddush haShem – sanctifying the divine name. Violating those rules amounts to khillul haShem – profaning that name.

Violations can take many forms, some more obvious than others. For example, our Torah instructs us to use true measurements – weights, measurements, coins, all must be accurate. Prevent cheating. In legal disputes we are cautioned to do justice “justly.” Tricking a witness in a trial, or manufacturing evidence against a litigant – even if you deeply believe him guilty – is unfair, and therefore prohibited. Acceptable conduct in family affairs has countless Mitzvos to be observed, including the rights and duties of wife and husband to each other, of parents and children to each other, and of all to the care of ill and dead family members.

Crime and punishment get dealt with in this section too. “One who strikes [wounds or kills] an animal shall pay for the damage. One who kills a human shall die.” But it takes two eye witnesses to convict the killer.

All these and many more Mitzvos can be fulfilled – or violated. Violating a principle of conduct in business, particularly when dealing with Gentiles, can bring serious trouble to the entire community. Every Jewish businessman carries the responsibility for the good or bad effect of his actions on all his people. The Hertz commentary quotes the story of the fellow in the boat drilling a hole under his seat. It’s only under his seat, but all will drown. A Jewish crook can give an open door to anti-Semites. That is definitely khillul haShem– blasphemy. And what about the opposite? Suppose we are doing right?

Our commentators frequently relate Kiddush haShem to Kiddush hakhayim – sanctifying life. Throughout our history, tragic events occurred that caused pious heroes to give up their lives for their faith, and they are said to have died al Kiddush haShem – for the sake of sanctifying the divine name. Whether they had a choice or not. Inquisitors demanded: “Convert or die.” Nazis and jihadis offer no alternative: “Kill the Jews!” Their victims are mourned with the righteous.

All-important in this principle is not death but life. Living in such a way as to sanctify the name of the G-d we worship involves fulfilling Mitzvos. From observing the occasions of our calendar – Sabbath, festivals, matzoh on Passover or fasting on Yom Kippur – to how we interact with other human beings, Jewish or Gentile. How we live our daily lives makes us aware of those Mitzvos, and carrying them out builds our character. Do we deal honestly in business? Do we respect our elders? Do we teach our children Torah? Do we help the poor? Do we support just causes? It is that kind of life that sanctifies G-d’s name. That kind of behavior sanctifies our lives. That is Kiddush haShem. Kiddush hakhayyim too.

This week and every week, today and every day, let the words of “Emor” remind us of our ongoing choice: profane or sanctify. Judaism offers us some practical help to make our lives count.

Posted in Jewish Blogs

|

Tagged Aaron, Cohanim, Emor, Fulfilling Mitzvos, Israel, jewish, Jewish Blogs, khillul haShem, Kiddush haShem, Leviticus, Mitzvos, Rabbi Baruch Cohon, Say, Torah, Torah Blogs, Torah Study, Violating Mitzvos

|

Comments Off on TO PROFANE OR TO SANCTIFY – “Emor” – Lev. 21-24 – by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

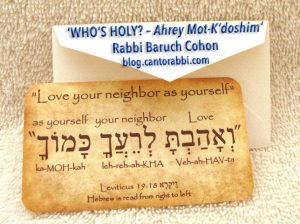

WHO’S HOLY? – Ahrey Mot-K’doshim Lev. 16-20 by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

WHO’S HOLY? – Ahrey Mot-K’doshim Lev. 16-20 by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

Just as they did last week, this week synagogue Torah readings cover two sections. They get combined except during leap years. In fact, they go together well. Last week’s double bill concentrated on the issues of purity and contamination. This week we read about laws and penalties.

First, however, the Torah lays out the conduct of the Yom Kippur service in the ancient sanctuary, including the sacrificial offerings, the conduct and clothing of the High Priest, and of course the scapegoat ritual.

Then come some detailed directions for slaughtering, preparing and eating meat. One outstanding provision is not to eat the blood. No “steak juice” cocktails allowed. Consuming an animal’s lifeblood had idolatrous associations, and we are told to pour it on the ground like water.

The remainder of the first section details actions to be avoided, citing them as typical of the corruption of Egypt. Included here are prohibited degrees of sexual contact, from incest to bestiality and, yes, homosexual relations. Polluting the Promised Land with such conduct would cause the land to “vomit you out, as it did the nation who was there before you.”

Warnings and prohibitions are not enough. The second section, called K’doshim – “Holy ones” – sets out penalties for violating these laws. We don’t find any prison time mentioned here. No fines, either. Minor infractions call for burnt offerings. Major violations incur execution or ostracism. Torah law may not be politically correct. Too bad. But what does all this strict punishment have to do with holiness?

In its very special way, the Torah defines Holiness before even going into detail about punishment. To be holy does not mean setting yourself apart from human society and its temptations. No ivory tower. Don’t try to be what’s called a “holy Joe.”

Just the opposite, in fact. Holiness requires that we deal justly and respectfully with each other. Honor your parents. Keep the Sabbath. Pay a day-worker before nightfall. Do not deceive your neighbor or lie, and never swear falsely because that is blasphemy. Do not curse the deaf, or place a stumbling block in the path of the blind.

Judges may well note the ruling: “Do not favor the person of the poor and do not glorify the person of the mighty. Judge your neighbor with justice.” Principles like those apply to non-court situations too, as we read about relations with someone whose actions you disapprove: “Do not hate your brother in your heart. Rebuke him, and do not bear sin because of him.”

Perhaps the most down-to-earth expression of holiness is this: “Do not take vengeance or bear a grudge against one of your people.” The classic examples of this disapproved conduct goes this way: Vengeance is when you ask to borrow your neighbor’s axe and he refuses; then next week he asks to borrow your ladder and you refuse, saying “You wouldn’t lend to me, so I’m not lending to you.” A grudge is when he refuses to lend you his axe, but when he comes to borrow your ladder you say: “Sure, here it is. You see? I’m not like you!”

Most famous of all the holiness teachings is the line “Love your neighbor as yourself.” To me, this means that first you need some self-love. If I have no respect for myself , what value is my love for my neighbor? Of course, the process goes both ways. By building a habit of treating other people right, we can also take some pride in our own lives.

Who is holy? Potentially, you and I.

Posted in Jewish Blogs

|

Tagged Ahrey Mot-K'doshim, Egypt, Family Values, holy, Israel, jewish, Jewish Blogs, K'doshim, Laws, Leviticus, Love Your Neighbor, Moses, penalties, Rabbi Baruch Cohon, Torah, Torah Blogs, Torah Study

|

Comments Off on WHO’S HOLY? – Ahrey Mot-K’doshim Lev. 16-20 by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

YOUR BANKRUPT BROTHER – Behar/Bekhukosai –Lev.25-27 – by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

YOUR BANKRUPT BROTHER – Behar/Bekhukosai —Lev.25-27 – by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

This week’s double reading covers the last three chapters in the Book of Leviticus, and also covers several subjects, so let’s single out just one. In the classic translation of Chapter 25 verse 35 we read: “If your brother be waxen poor…” Waxen poor??? Like a bad face job? No, that is the accepted Elizabethan English for the Hebrew word yamukh, which means a personal or economic downfall. More about yamukhlater. What we can learn initially from this section is how to treat that brother.

First the Torah tells us that if this poor loser comes to you for help, you are to strengthen him. If he is a native Jew, or a convert or, as Ibn Ezra includes, a resident alien, let him live. Help him live. Don’t let him starve. As the Hertz commentary points out, no other society had such rules. Not only in the days of the Torah over 3,000 years ago, but right up to the Roman emperor Constantine who instituted poor-relief in the year 315. Even Constantine’s legislation was repealed by Justinian a couple of centuries later. And notice that the Torah directs this rule to the individual, not the state. This is not a “stimulus package.” It is an Israelite’s duty to save a neighbor.

Secondly, we will read that we are not to take interest or usury from him. Yes, he needs a loan. He needs money to feed himself and his family. He needs money to start over, to get back on his feet. If I want to charge him interest, don’t I have a right to it? No, says the Torah. “Revere G-d, and let your brother live with you.” Don’t try to profit from his loss. Both in Biblical and Rabbinic law, a fine line separates legitimate interest – neshekh —from exorbitant usury —tarbis. Here both are prohibited.

Ever been to a Jewish Free Loan office? Every Jewish community of any size has one. In Los Angeles where I live, the JFL lends for economic and medical emergencies, or to help a small enterprise get started, and its borrowers are not all Jews either. Of the thousands of loans on their books, they show a repayment record “in excess of 99%.” Not a bad record. That is Leviticus in action.

Now back to yamukh. Notice that the text specifies a downfall. This current condition was not necessarily always there; this fellow was not always broke. Maybe he was once as successful as you are. Maybe he just made some mistakes. Maybe he got robbed or cheated. Or maybe he is not very smart. This is not a condition he planned. No “entitlements” here. He is out of luck and out of money. Your job is to help him if you can. Of course we can ask “what if this fellow makes a racket out of his poverty? Do you still have to help him?” A legitimate question to be sure. The Book of Leviticus does not treat that possibility, but Talmudic justice would put it in the category of deceit. Last week we read commandments like “Do not deceive your neighbor or lie.” Using the shelter of bankruptcy to take advantage of other people’s generosity is also a form of deceit. Not worthy of help.

Here we are dealing with something more positive. The valuable message of this week’s reading is our personal responsibility to extend a helping hand in an emergency. The Klee Yokor commentary discusses the definite prohibition on taking interest for your help in this situation. Whatever you give this down-and-outer is not a business loan. By contrast, if a rich man asks you for money, go ahead and charge interest. Says the Klee Yokor: “Whoever owns a business always looks for G-d’s help, because of the doubt: will he profit or not?” So he borrows money. The lender also takes a risk, so he is entitled to charge interest. “But,” says the commentary,“seek out the meaning here. The basic purpose [of this ruling] is to forbid usury.” Your unfortunate brother must not be your victim.

“V’khai akhikha — Let your brother live.”