COUNT ME IN, OR OUT —BAMIDBAR – Numbers 1:1—4:20, by Rabbi Baruch Cohon

This week we will read about a census. Moses had to confirm the numbers of the people he led, specifically men over 20 who qualified for military service. He also had to assign tribal leaders, lay out the camp, and delegate tasks to the tribe of Levi, whose duties were not military but religious.

Did this census take place on some special holiday? Not at all. We learn that it was on the first day of the month of Iyyar in the second year out of Egypt. And we know they crossed the Red Sea on the 7th day of Passover, the 21st of Nisan. So we find a period of 12 months and 10 days between countings. When the Israelites left Egypt, their draft-age men numbered 603,550. They walked through the desert for six weeks, received the Torah at Mount Sinai, shlepped on some 11 more months — and how many are left? 603,550. No more, no less. Coincidence? For every older man who died on that trek, did one 19-year-old turn 20? Looks that way, because that census was not a documented process. It was poll tax. Each man brought half a shekel, and that’s how he got counted. Now, before designating where each tribe would camp, Moses had to be sure that camp would be defended.

Where did Moses have to do all this? Bamidbar – in the desert. That word, that barren location, identifies not only this week’s reading but this entire book of the Torah. “Desert” is the Hebrew name. “Numbers” in English. It identifies the climate of our story. Again we register. Again we report to leaders. Again we take orders. Again our people must count us – and count on us – to defend them from violent enemies. Kol yo-tzey tzava – All who go to the Army. All who go to the IDF. All who brave the international desert. Count them in. Any who don’t – count them out.

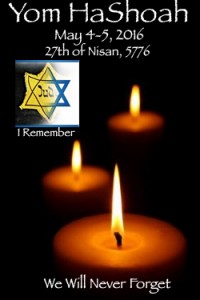

At this season we do a great deal of counting. In fact, this Shabos we conclude the seven weeks of s’firas ha-omer – “counting the Omer,” the 49 days following Passover when the special offering called the Omer was waved before G-d in anticipation of the 50th day, Shavuoth, when we received the Torah. This year, Shavuoth begins Saturday night as Shabos ends. We like to say that we count our days in order to make our days count. Indeed we should.

We should take note, too, of the different Hebrew words for the counting process. The Torah commands us to count the days with the word v’sofarta from the root safar which is also the root of sefer – a book, and sippur – a story. Interestingly enough, by completing the count we produce a total, which is not a story, not a book, but sakh hakol – everything. And an accountant in Hebrew is not a sofaer; that’s a scribe. The accountant is called an orekh kheshbon – one who verifies the sum by his calculation, kheshbon coming from the root word khoshev – to think.

There’s more to it. S’firah refers to counting days, yes. But here in the very second verse of Numbers, Moses is told: s’u es rosh b’ney Yisroel – literally “lift the head of the sons of Israel.” Counting people, particularly the people of Israel, must involve respecting each individual. Lifting each head high. The Klee Yokor commentary states that this choice of words indicates a certain value and a certain responsibility that makes the Jewish people unique, because of hashgakha protees – individual supervision, the concept that G-d cares about each one of us, while His attention to other nations is as groups. Could that kind of attention apply to all humans? After all, we have to remember that G-d is unlimited. Or perhaps we are singled out – chosen, if you will – for personal responsibility.

Furthermore, in the same verse, Moses is directed to count them b’mishp’khosom – in their families. Recognizing the family as the basic unit of any civilization, tribal in Moses’ day, industrial later. Threatened now. Every one of those 603,550 men represented his family, and had to risk his life for them.

Did we ever leave the desert? Or did the desert ever leave us? Past enemies made deserts out of verdant countryside. Today’s enemies bring their desert desperation and their desert violence with them. We still need to be counted. Are we all registered? Do we have leaders ready to defend us? We may not be confined to the desert any more, but we should be able to count — on each other.

Polls and surveys publish all kinds of numbers about us. What percentage of which generation is religiously observant? How many American Jews support Israel? Is the world Jewish population rising or falling? We can find numbers everywhere. Just lately we learn about whole communities in South America becoming Jewish – an estimated 60,000 of them. (one for every 10 of Moses’ soldiers!) Will they in fact add new purpose and power to our future?

And on the other hand when we look for each other, if we find bitter antagonism both political and religious, we may feel that we are in the desert, divided, confused, lost.

Bamidbor/Numbers can wake us to realize that we are in fact the same people who left Egypt so many centuries ago. Whether we are 603,550 or a few million, we face the same challenges and inherit the same duty. Wherever we live, we must count. On each other.

Kol yo-tzey tzava – Count us in.